Although Durfee & Peck tokens are not extremely rare, I acquired my first recently at the 2003 NTCA national show in Omaha. Remembering that I had read of the token series in one of my exonumia books, I began to search my exonumia library, for information on them. Finding very little information in my books, I set out to find out for myself the historical setting of the tokens, the place where they were made, and who used them, where and how they were used. This writing is the result of that search, and I hope that it will add to the available written record concerning the background of Durfee & Peck, Indian traders.

Fuld implies on page 208 of Token Collector Pages, that the Durfee & Peck tokens may have been used at Forts Union and Fort Buford. This was my starting point for research. I set out to verify where D&P had trading posts that might have used tokens (human fallibilities have surely made my list too short). I did verify that D&P had trading posts at both Ft. Union, D.T. and at Ft. Buford, D.T. I have been unable to verify Fuld’s implication that the tokens were used at those two locations. I suspect that the tokens were used at many of their trading posts. In fact, I suspect D&P intentionally ordered tokens without a location stated on them, in order to be able to use them at many trading posts. The best proof would be the discovery of one of the tokens “in situ” at an archeological dig near one of the forts.

Fur trading posts in 1868 were inherently transitory, and a single outpost might last 12 months or less. Since Fuld never states that the tokens were used at Forts Union and Buford, but hints at this, I gave that idea free rein and have examined those two posts in detail. Ft. Union, D.T. was a privately built and run fur trading post, not a military post. However, Fort Buford, D.T. was built and run, as a military post of the U.S. Army.

Vignette

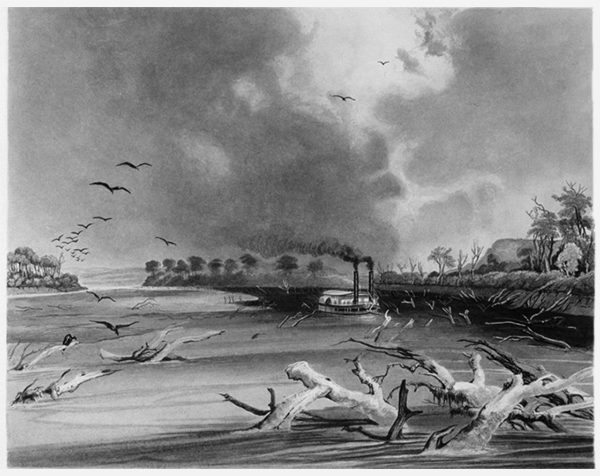

The year is 1867, the place is the civilian trading post named Fort Union, Dakota Territory. A matte of muted green native grasses stands knee high along river’s banks. On the first terrace above the water can be seen a few Indian teepees and small campfires, seemingly randomly spaced from near the river’s edge to past the log fortifications. Through the smoky haze of this early April morning, a side-wheel steamship churns westward against the current.

The year is 1867, the place is the civilian trading post named Fort Union, Dakota Territory. A matte of muted green native grasses stands knee high along river’s banks. On the first terrace above the water can be seen a few Indian teepees and small campfires, seemingly randomly spaced from near the river’s edge to past the log fortifications. Through the smoky haze of this early April morning, a side-wheel steamship churns westward against the current.

The vessel stays in the center channel of the Missouri River and sounds its whistle…. just as the American flags of the fort are visible. The steamship whistle speaks again: WHOOOOOO!! WHOOOOO!!! Muffled baritone voices can be heard across the water, then suddenly…. BOOM!!! …the fort’s cannon fire a welcoming salute! As the steamship’s engines reduce power, clouds of smoke rise from the steamer’s twin stacks, and the vessel carefully steers between the sand bars toward the Missouri’s shore.

Early Fur Trade and Indian Trade in North America

The Hudson’s Bay Company had been the earliest fur traders of note in the great lakes area. Some even joked that the letters HBC meant “Here before God”! The U.S. Government became involved in the Indian trade in the late 1700’s, and from 1796 until 1822 the federal government operated a “factory system”, which was a series of trading posts that were government supported, somewhat modeled after HBC. The federal employees that ran these were called “factors” and thus the name factories.

These factories stocked Indian goods, and engaged in direct trade with the Indian tribes for pelts, and furs, in the hopes that this would ingratiate the tribes to the federal government. In 1803 Thomas Jefferson proposed a new direction for the factories, which they might extend enough credit to the Indians that they might create massive debts, and thus their only means of undoing the debt with their limited means would be to cede land to the government. The factory system as it existed was pretty much a monopoly, effectively eliminating private trading with the Indians. Also, the law makers of the United States prior to 1865, saw no difference between the fur trade, and Indian trade, they were one and the same virtually and legally.

In 1822, revisions were made to the existing Indian-fur trading laws. The Indian Office was allowed to issue licenses to tide west of the Mississippi for up to 7 years rather than the earlier 2 year limit. Maximum trading bonds were raised from one thousand to five thousand dollars. Also the special superintendent of Indian Affairs would be required to reside in St. Louis, in recognition of that cities large role in the Indian-fur trading business.

In June of 1834, Congress created the Department of Indian Affairs. This new Department had offices in Washington and sent Indian agents and subagents into the field to live with, or near the tribes under their jurisdiction. The president appointed these agents to 4 year terms with the consent of Congress. Regulatory laws dictated that Indian traders file bonds of several thousand dollars before being licensed. Licenses set specific locations for trading posts, and the traders were forbidden from traveling around the countryside looking for customers.

Brief History of Fur Trading in Upper Missouri Area

Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) was chartered in 1670 by British monarch Charles II (ruled 1660-1685). HBC merged with the North West Company (NWC) (founded 1784) in 1821, creating the largest fur trading business in area. As with many mergers, many lost their jobs after the merger, three men who lost jobs, Kenneth McKenzie, William Laidlaw and Daniel Lamont, joined Joseph Renville, James Kipp and Robert Dickson to form a new trading company, dubbed “Columbia Fur Company” in 1821, whose goal was to operate mainly south of the Canadian border. Columbia Fur Company (CFC) faced tough competition not only from HBC, but also from John Jacob Astor’s “American Fur Company” (AFC), which had opened its St. Louis office in 1822. CFC built four posts in the Minnesota valley, more posts at Lake Traverse, several along the Missouri River, and at Green Bay on the western shore of Lake Michigan.

By 1827, Astor’s American Fur Co. could no longer stand by and allow McKenzie’s CFC to cut into the limited resources. So in July of 1827, Astor’s AFC bought out the Columbian Fur Company, keeping the principals, and renaming it the western branch, or “The Upper Missouri Outfit” (UMO), which would be the group that would build Fort Union, D.T. some 18 months later. The chief executive of the newly formed UMO was Pierre Chouteau, Jr., a man of great organizational abilities, descended from one of St. Louis’ founding French families. (Those of you who collect Indian Peace medals may recognize the name Pierre Chouteau, as there are privately minted Indian peace medals dated 1843, which his company produced and presented to Indian chiefs. There are also fake Chouteau medals being sold recently on eBay.)

Forts Union and Buford were both located on the upper Missouri River, on the path that Lewis and Clark trod in their 1814 journey.

D&P – Brothers In Law

E. H. Durfee was the elder of the two partners of Durfee & Peck being 3 years older than C. H. Peck. Each man married one of the Higbie sisters of Penfield, N.Y., making them brothers-in-law.

“Commander” Elias Hicks Durfee

Elias Hicks Durfee was born on December 29, 1828 in Marion, Wayne County, New York, to Elias Durfee (1796-1864) and Mercy Mason (1802-?). The Durfee family had come from Rhode Island, where they had lived since the 1770s. Elias Hicks Durfee (b: 1828) married Lucia Marian Higbie (1832-1906) on Nov. 24, 1852 in Penfield, N.Y. Elias and Lucia Durfee had one child, Charles Higbie Durfee born June 8, 1855 in Marion, N.Y. and died Jan. 28, 1902 in Kansas City, MO.

E. H. Durfee came to Leavenworth, Kansas in 1861 from New York. Durfee’s office in Leavenworth was located at No. 48 Main Street in 1867. Durfee was the elder of the two partners; he married the elder sister of the two Higbie girls, and married 4 years before Peck. Fuld suggests that Durfee was the senior partner of Durfee and Peck, and I agree. Elias Hicks Durfee died September 13, 1875 in Leavenworth, Kansas (age 46). Unfortunately I have been unable to find any photograph or painting of Mr. Durfee.

“Colonel” Campbell Kennedy Peck

Campbell Kennedy Peck was born on April 8, 1831 to Nathan Peck and Nancy (Kennedy) Peck in Troy, New York. Campbell married Helen Augusta Higbie (1836-1905) of Penfield, N.Y. in 1856, and they had two children: Nellie Peck born on April 24, 1859 and Cady Kennedy Peck born on August 28, 1862 both in Penfield, N.Y. Campbell Kennedy Peck died December 3, 1879 (age 48). Fort Peck was named for C. K. Peck. It was established as a fur trading post by Abel Farwell for Durfee & Peck in 1866-67. From 1873 until 1879 the government used a portion of the fort as the Fort Peck Indian Agency. The site of Ft. Peck was abandoned in 1879, and now is under the waters of Fort Peck Reservoir near Poplar. Unfortunately I have been unable to find any photograph of painting of Mr. Peck.

Scovill Manufacturing Company

Fuld states that all the Durfee & Peck tokens, as well as the E. H. Durfee tokens were struck by the Scovill Manufacturing Company of Waterbury, Connecticut, and those records exist that verify the exact shipping dates and locations.

Fuld notes that his belief is that a die-cutter named Ellis (working for Scovill) is believed to have cut the D&P dies, and that a different die-cutter name Wumer cut the G. W. Felt dies. From the unusual representation of a buffalo on the D&P token, we could hypothesize that die-cutter Ellis not only did not have a photograph of a bison to work from, most likely he had never seen a bison in the flesh. Possibly he was working from period engravings and artwork which he had seen, along with verbal descriptions. The bison depicted on the token appears to have a very long tail!

The Tokens’ Designs

The idea of having a pictorial representation on the tokens was possibly to enable the Indians who used the tokens, to discern the three different values, since they could (for the most part) not read English. The selection of the subjects of the three pictorials, were scenes that must have been important, and easily recognizable to the Indians.

The subjects selected were “the big canoe” (as the Indians called it) or side wheel steamer for the half dollar token, the mounted Indian buffalo hunter for the dollar token, and the running buffalo for the quarter dollar token. The obverse and reverse both have dentiled borders. The wording on the tokens is styled in a beautiful serif font. To add to the beauty, curved lettering spans the center of the tokens. All of the tokens are highly detailed, and beautifully done. The representation of the steamship is quite realistic, but the representation of the buffalo is naive, primitive, and charming.

The Long Trip Northwest for the Tokens

Fuld states that the D&P tokens were shipped by Scoville in Connecticut to the D&P office at St. Louis, Missouri.

The trip from Waterbury, Connecticut where the tokens were struck, to St. Louis, Missouri, and thence up the Missouri River to Fort Union, Dakota Territory, is a total of about 1,900 miles. I have not found any record of how they were transported from Waterbury to St. Louis; however the typical trips from St. Louis to Dakota Territory are well documented.

The supply trips to Ft. Union were generally made in the spring each year, as the river navigation was closed from November to March. During the spring, the rapid current of the Missouri River was swollen by spring rains, and melting snows, making the waters a swirling mass of snags, logjams, dead trees and debris. This meant that the pilot of the boats going upstream had to be not only extremely vigilant, but it helped if he had years of experience in this type of hazardous navigation. During the year 1834, when German Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied and his entourage were making the journey from St. Louis to Ft. Union on the steamship Yellowstone, it took 75 days for the one way trip upstream. A tradition at Ft. Union was to fire a volley as a salute for any approaching or departing boat, with one of the small cannon.

After unloading the supplies for the fort from the steamship, the furs and pelts from the fort were loaded back on the boat. Buffalo robes were packed (at the fort prior to departure) in pressed bales (hide presses were located just outside the palisade). In the year 1834, the steamer Yellowstone on its first trip back downstream to St. Louis carried eight thousand buffalo robes, and about 6,200 wolf and fox hides. The yearly trade for Ft. Union at that time was about 42,000 buffalo robes per year.

- The Ghost Town Tokens of Thurber, Texas - June 2, 2013

- Durfee & Peck’s Indian Trader Tokens - May 19, 2013

any exact dates when Fort Browning on the Milk River started to be built.