It was the 1843 Copper Rush on Michigan’s Keenesaw Peninsula that the towns of Hancock and Houghton owe their existence. Long known about by Native Americans for millennia, the area possessed rich deposits of copper and silver ores.

With primitive mining activities dating back as far as 7,000 years, it is the only known place on Earth where 97% pure copper can be literally pulled from the ground. And in the United States, it is the only geographic area where evidence of prehistoric copper mining has been confirmed.

Beginning in the 1840s, the metals on the peninsula began to be extracted on an industrial scale. Starting out as opposing points at opposite shores, Hancock and Houghton’s future locations were convenient places for miners to launch their canoes and cross Portage Lake.

Within a few years after the Michigan’s Copper Rush started, deposits were discovered in close proximity to both shores. Settlements arose, and people flocked to the region.

As with other areas on the peninsula, claims were quickly staked, mines were rapidly developed, and people seeking economic opportunity brisky migrated to the two locales. Overnight populations along the shores began to skyrocket.

As with the deluge of people, mining companies also quickly moved in, and the area rapidly became industrialized. With the boom of people, so too did an economic boom of mining industry ensue. Soon mine shafts traversed the countryside, and copper processing facilities dotted the landscape.

With the onslaught of new settlers and businesses, two towns sprouted on opposing sides of the lake. Merchants and proprietors moved in, and demand quickly increased for an efficient means to cross the waterway. At first, a single private ferry service was established to link the two populations. By 1853, regular warm season ferry service provided connections between the two towns.

As the towns’ populations blossomed, so too did the number of ferry companies providing service across the lake. Very soon, however, even multitudes of ferry boats could no longer keep up with the demand. Winter ice, in addition to the area’s rapid growth, compounded the transportation challenge. Crossings by ferry service simply couldn’t keep up with the number of people and goods needing to cross the lake.

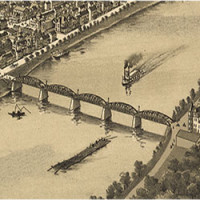

By the 1870s the towns’ elders began to explore the feasibility of bridging the two locations. In 1875, town officials from each side approved the construction of a bridge, and partners George Sheldon and James Edwards were commissioned for the undertaking. Raising funds from investors and sales of stock, the partners formed the Portage Lake Bridge Company, and construction began in the spring of that year.

With an initial investment of $10,000 and a span to accomodate two-way traffic, a wooden bridge was designed with an iron-swing at its center for boats to pass. Less than 8 months after ground-breaking, the bridge officially opened for business on Christmas day of 1875.

The towns’ inhabitants lauded its opening — but their elation was shortlived.

The very next day, a freakish landslide occurred from a bluff overlooking the bridge, and 200 feet of its north span was smashed. Once again, inhabitants found themselves having to rely on overtaxed ferry service while the span was rebuilt. Costing an additional $5000 to repair, the bridge finally reopened four months later in April 1876.

For the next 15 years, the span operated as a private toll bridge, and the once prosperous and prolific ferry companies faded into extinction.

Despite being constructed of wood, and safety often called into question, the bridge served as a critical artery that connected the two towns.

By 1891 however, citizens of both towns had become disgusted with the bridge’s owners. Much of the citizenry had come to the realization that the tolls they had been paying had long covered the costs for its initial construction. With the rise of public outcry, the company relinquished ownership of the bridge, and deeded the span over to Houghton County.

Upon possession, the county abolished its tolls, raised the bridge’s deck, and citizens were free to cross at will.

The life of the bridge however was not to last. A mere 4 years after the county took possession, a steel bridge was erected and the wooden bridge was torn down.

Over the next 70 years the region’s copper industries continued to flourish. By the 1970s, however, the towns’ economic booms had waned. No longer were the copper veins economically feasible to mine.

However, economic prospects for the region have recently improved. As the value of the world’s copper prices have steadily increased over the last decade, so too have the prospects of copper companies reopening mines in the area.

Numismatic Specimens

There exist four known varieties of the Portage Lake Bridge Co. token. Three were struck in vulcanized rubber, and fourth sruck in copper. The table below describes the varieties:

Illustrated below is an MI470-A variety. Measuring 24mm in diameter, it was struck in vulcanized rubber. The token was issued to pedestrians who wished to cross the bridge on foot, and had a value of 1-cent. One token provided passage for a single one-way crossing.

Despite being over nearly 140 years old, the specimen exhibits beautiful coloring. The specimen is AU in grade and posseses a pleasing chocolate patinia.

Aaron Packard ![]()

Notes and Sources

-

The Atwood-Coffee Catalogue, Sixth Edition, Volume I, John M. Coffee and Harold V. Ford, AVA

-

The Atwood-Coffee Catalogue, Fourth Edition, Volume II, John M. Coffee, AVA

-

City of Hancock, Michigan Digital Archives

-

Michigan Technological University, Digital Archives

-

The Copper Range Railroad, ‘The history of the three bridges to span the canal between Houghton and Hancock,’ Kevin E. Musser, 1997

-

Timeline of Michigan Copper Mining Prehistory to 1850, Keweenaw National Historic Park, National Park Service, United States

-

‘The Portage Lake Volcanics (Middle Keweenawan) on Isle Royale Michigan,’ N. King Huber, 1973

-

The State of Our Knowledge About Ancient Copper Mining in Michigan,’ Susan R. Martin, The Michigan Archaeologist 41(2-3):119-138, 1995

-

‘Notes From the Copper Region,’ Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Robert E. Clarke, March 1853, pgs.433-449

-

‘A Mining Rush in the Upper Peninsula,’ The New York Times, Emily Lambert, May 24 2012

-

The Library of Congress Digital Archives

- New York’s Crystal Palace & The H.B. West Tokens - November 6, 2019

- Edward Aschermann’s Cigar & Tobacco Tokens - November 2, 2019

- George T. Hussey & His Special Message Tokens - October 30, 2019

I really enjoyed your research into a fascinating niche of history, and your essay on these interesting objects from the day!

Ernie Nagy

President

Michigan Token and Medal Society

Thanks Ernie. Glad you enjoyed the article!